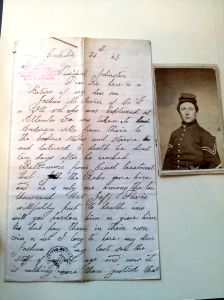

This letter, written by the mother of Union soldier Joshua M. Irvin, a POW at Andersonville who died not long after his release, is one of many that discusses how Jefferson Davis was personally responsible for the horrors of all Confederate prison camps, and should be punished for causing the deaths of so many Union men.

Virtually all of the anti-pardon letters sent to Andrew Johnson were fascinating to read through. The boxes contained a mixture of letters written by Northern citizens and Union veterans, all expressing absolute hatred towards Davis. What surprised me most about the letters was the range of solutions and answer to the question, “What should be done with Jefferson Davis?” My initial thought was that all, or at least a majority, would be calling for his immediate trial and execution. While I did find a fair number who wrote those very words, they constituted a smaller percentage than I anticipated. This unexpected find helped me contemplate how these particular individuals thought in the first months and the first year after Appomattox, and made me question why they wanted something other than Davis’ trial and execution.

Mr. Bernard Glancy Jr. of Danbury Connecticut wrote to President Johnson on June 6, 1865, with a rather long letter detailing his position on the Davis matter. “After serving the term of almost four years in the cause of my country for the purpose of putting down the Rebellion and enforcing our laws against those arch traitors in Rebellion against us, … I have been spared to see its end and to see the capture of its various rebel leaders who were trying to overthrow our glorious Union and trample our beautiful and starry emblem in the dust,” he wrote. A survivor of Andersonville, he discussed at length the horrors of the prison and the intent of the “traitorous foes” to do “all that they could to starve us to death.” “Oh it made my heart leap with joy when I read of the capture of that arch traitor Jeff Davis while trying to escape in the garb of a woman and I would like to have a hand in building his scaffold …. I would like to be the one to lend a helping hand for I long to see him hang and I want to see him hang high for the sooner all such men are put to death the sooner we will enjoy happiness and the sooner we will have peace throughout our land.” Glancy concluded his letter asking Johnson to write him if there was any “chance for [him] to render [his] services in helping to build that scaffold,” as it would be a “great and noble duty to perform.”

A concerned citizen from Pontiac, Illinois wrote to Johnson on May 20, 1865, asking him to follow through on what he had said on January 21, 1861. Attached to the letter was a newspaper clipping with an excerpt from Johnson’s remarks in the Senate, where he stood after Davis had “terminated” himself from his congressional duties, shouting, “Were I the President of the United States, I would have you tried for treason, and, upon conviction, would hang you, so help me God!”

J.H. Heughey from Illinois requested on June 19, 1865, that “Jeff Davis and others found guilty of treason be hanged on the 4th of July next. Such an occurrence would constitute an important item in American history.” Another citizen from Massachusetts also suggested to hang Davis and his fellow conspirators on the 4th of July, as it would signify a great event in the nation’s history.

One man offered to build the gallows for Davis and included a drawing of how he would construct them and with what type of wood. Another offered to exercise his profession, a professional rope maker, and make the rope, free of charge, that would be used to hang Davis.

Majority of those calling for Davis’ swift trial and execution were primarily Union veterans, with some Northern civilians thrown into the mix. After reading all of the letters, though, I have concluded that Northern civilians differed on how to deal with the Davis question. While they all expressed their hatred for the man and what he stood for, less of them actively called for his execution but rather used his unusual situation to help the recovering nation in a positive way.

Washington Messill, a citizen in Washington, D.C., suggested on May 19, 1865, to not “hang Davis now,” but to let him live a few years, “put him in a strong iron cage,” and “conduct him then [around] the states with the same dress he was taken in at one dollar the sight.” The collected money would then be given to “all injured soldiers both north and south.”

J.H. Cheeseman from Oakly, Illinois wrote that “having received the news of the capture of the vile traitor Jefferson Davis, the thief and would be President of the Rebellion, it struck me, that to take him on [an] expedition through the Northern States, just as he was capture[d], in female attire, it [would] raise the funds to pay the National debt, for most every one would pay fifty cents or a dollar to see him. I have heard several say that they would already, and I should judge there are many more, it would be an easy way of making him help pay what he has helped to contract.” As part of this circus-like act, Cheeseman suggested to brand Davis on the forehead with “M for murder; and D for devil.”

Twelve year old Lilla Sibley from Lawrence, Massachusetts requested that Johnson “send Jeff Davis around to the loyal states and have him exhipited [sic] that we may pay 50 cents or a dollar apiece and have him carried to the metroplious [sic] of every state. … My father … works hard every day and he will pay enough to see that scoundrel who has caused so much blood to be shed and so much money to be spent and if you will have him sent around, the money that is received will help pay off the debt.” A man from Ohio echoed similar sentiments, saying that “as poor as I am [I] would give five dollars to see him, so that I could say I had seen a would be president.”

A loyal woman of Massachusetts wrote that “the North think that Jeff Davis might [lower] a large portion of the national debt by being exhibited in his costume in all the cities.” A man from Michigan suggested to have Davis “dressed the same as when captured,” and that the “proceeds of sale be appropriated in paying the expense of capture.” “It would meet with a ready sale here,” he wrote. James B. Smith of New York penned that “by request of a number of citizens of this city, it is respectfully suggested to your Excellency that the arch traitor Jeff Davis be brought to the city in his petticoat regimentals, and paraded, for the education of the public, through Broadway.”

These excerpts only represent a portion of the larger collection, but do show the difference between Northern civilians and Union veterans and the battle over what to do with Jefferson Davis. What ‘solution’ would better heal the nation and create a lasting peace, while at the same time attaining justice for the traitors? Would it be his trial, conviction, and execution? Or would it be parading him around like a circus freak, resulting in absolute humiliation for the Confederacy’s leader and cause? A tricky balance lay between healing and justice, with a range of possibilities on how to achieve both. But with no real precedent or guide on how to exactly do so, the question of what to do with good ol’ Jeffy D remained.