The five mystery boxes in Record Group 94 (which were much easier to find this time compared to last) that contain the petition letters sent to Andrew Johnson arguing for or against the pardoning of Jefferson Davis are absolutely fascinating. I find myself becoming so immersed in the letters and reading/deciphering them that it takes me a few hours to go through only a few folders. However, doing so and spending an incredible amount of time sifting through the letters has proven to be such a rewarding experience. In this blog, I will highlight the general conclusions I have drawn after reading the petition letters, and then in the next blog I will focus on a few specific letters that I found to be the most intriguing and representative of the sentiment felt by Northerners to the ex-president.

The five box collection was divided into petition letters urging Johnson to pardon Davis and those arguing to follow through on the trial and possible execution. The former was contained in three boxes, all divided up by state, and the latter was contained in two boxes, also divided up by state.

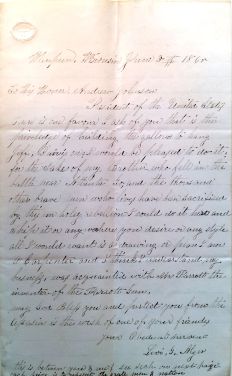

The letters sent to Johnson advocating Davis’ pardoning and release from jail were primarily focused around a theme I had never given much thought to: religion. Surprisingly, almost all of the letters contained religious overtones and appealed to Johnson’s moral side in granting Davis clemency and mercy. “The high privilege which God has given you… be merciful,” wrote a George McClellan from Florida. “Mr. Johnson, be like your God, “full of compassion and gracious long sufferings plenteous in Mercy,”” pleaded Mrs. M.S. Kimbrough from Georgia. A Mrs. M.A. Foard from Delaware penned a letter to Johnson claiming Davis was “great” man, so “noble and righteous,” and that he is not to blame for any Southern ‘crimes.’ “Will you deal unmercifully, unrighteous with him for just one error? God forbid. Is not cruelty the greatest of all crimes?” she wrote. An anonymous citizen from Aiden, Ohio pleaded with Johnson, writing “I appeal to you as a Christian… May God in his infinite mercy, carry my appeal to your heart and may you in tender compassion, at once grant one.”

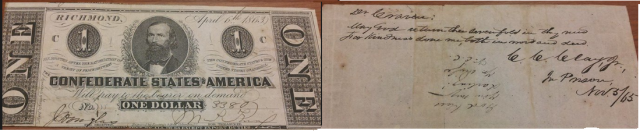

The letters sent to Johnson in favoring of not pardoning Davis took a more drastic turn than I initially anticipated. I expected all Northerners, citizens and veterans alike, to be calling for Davis’ trial and execution, or at least suggesting life in prison. While that was the case in a great deal of the letters, it was not the case for a surprising number of them. (This was a difference that I will talk more extensively about in the next blog). What I did find were solutions to the “Davis problem,” ways to not only punish Davis and humiliate him, but to put his imprisonment to good use for the nation. “Don[t] hang Jeff Davis now, but put him in a strong iron cage, … conduct him then [around] the states with the same dress he was taken in at one dollar the sight and give the same to all injured soldiers both north and south of which they so much need the debt…” wrote a man on May 19, 1865, in Washington, D.C. A resident of Illinois, J.H. Cheeseman penned Johnson in May 1865, with the request to take Davis on an “expedition through the Northern States, just as he was capture[d], in female attire, it [would] raise the funds to pay the National debt, for most every one would pay fifty cents or a dollar to see him.” Women, even, were voicing their opinions on what to do with “Old Jeff.” “Many others of the Northern Ladies would be mighty gratified to have Old Jeff put into an iron safe and exhibited through the country to help pay the public debt…” wrote a Mrs. B.S. May from South Boston, Massachusetts on May 19, 1865. One man from Ohio asserted that the national debt would be paid in a “short time” if Davis were to be “cage[d] up” and shipped around the North.

Similar language and sentiment regarding locking Davis up in a cage and sending him around the North to accrue money for the National debt was found in a surprising number of letters. I found it especially intriguing that these citizens were creating practical uses for Davis while he was still in Federal custody. Their ingenuity amazed me, and certainly adds another layer on determining what, exactly, to do with Traitor Jeff.

These brief excerpts from these various letters, from both the North and the South, give a glimpse into the religious imagery that citizens evoked when trying to push Johnson along to pardoning Davis, and also into other solutions for Davis that strike a balance (somewhat) between healing and justice. As I mentioned above, the next blog will focus on the “juicier” letters I found, ones that really accentuate this religious theme I identified and the letters from Union veterans pushing for Davis to hang from the gallows.

Until next time…